Match the fidelity of the prototype to the fidelity of the question.

Even experienced human-centered design teams sometimes face a dilemma: how realistic should they make their prototype? Should they go for high fidelity—something which looks and feels just like a finished product? Or low fidelity, like a rough paper sketch? Or should it be something in-between, like a basic click-through prototype or rough physical mockup?

First, we need to zoom out slightly. We prototype in order to learn from people in research. So before an IDEO team starts prototyping, we will often start by listing our learning goals, which might be very broad—or quite specific. Then we craft our prototypes to help us with those learning goals. As former IDEO Partner Diego Rodriguez put it, “a prototype is a question embodied.”

That’s why my mantra is: match the fidelity of the prototype to the fidelity of the question.

Okay, but what makes a question high or low fidelity? It’s not how specific or detailed the question is—or how complex the technology or implementation is. A low fidelity question is anything a research participant can easily answer. If we have nuanced questions which are experiential, behavioral, or contextual, those are high fidelity.

What if iPad?

On a project to redesign the retail experience for a chain of tire stores, an IDEO team made a full-scale foamcore store mockup in our Chicago studio. They wanted to learn about layout, workflow and salesperson interactions in a format that could be quickly reconfigured.

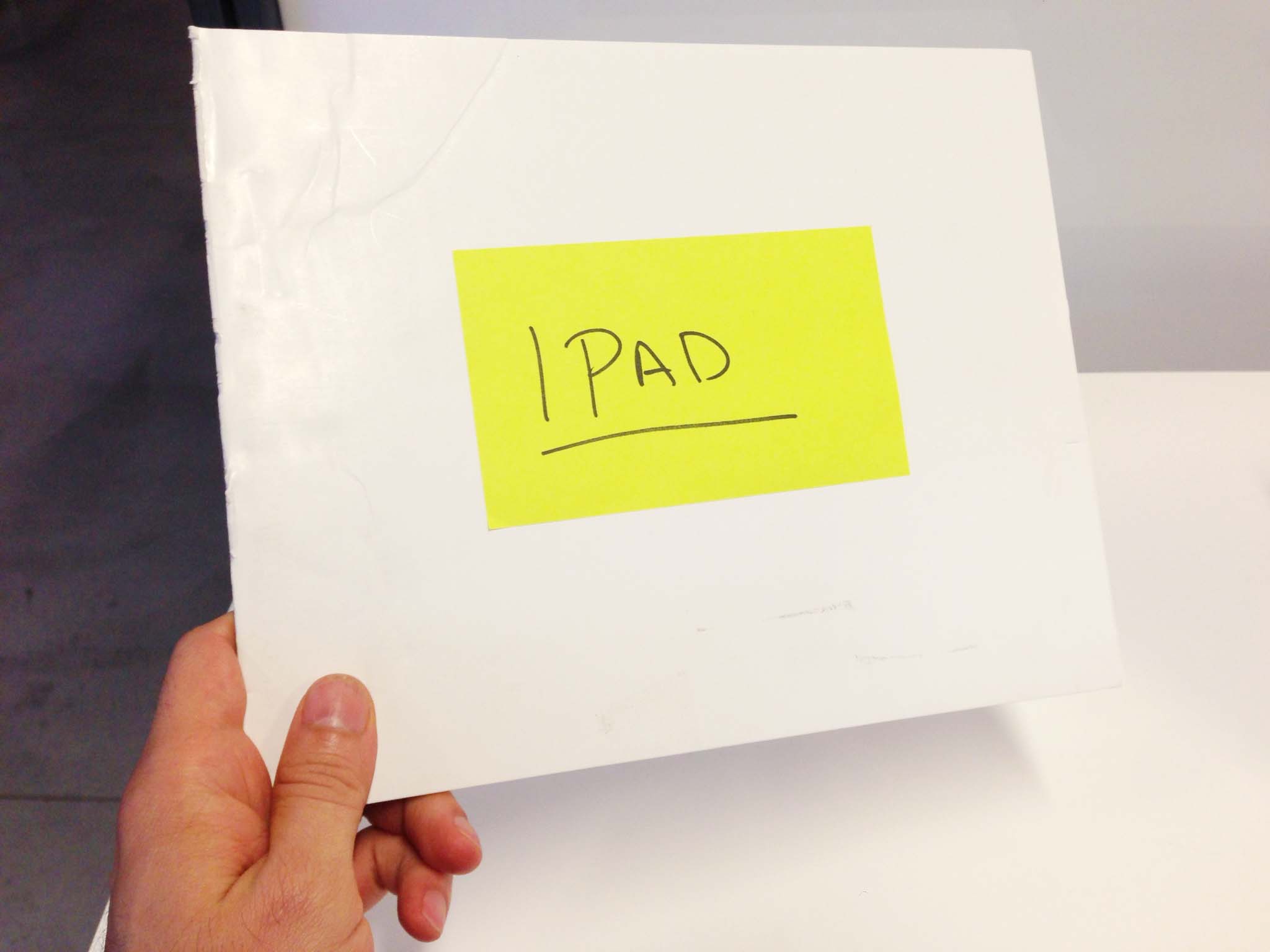

That’s where I came across a piece of roughly cut foamcore with the word “iPad” written in Sharpie. The team was trying to understand how to facilitate collaboration between the salesperson and customer as they discussed the tradeoffs of various tires: should they use a tablet so they can walk around the store and discuss, or a larger shared screen they can both see?

The designers easily could have used a real iPad with a mocked up UI, but it would have invited feedback on the interface rather than the main question: what role should screens play in-store? When users looked at the blank foamcore and asked “what would be on the iPad?” it opened the door for the classic researcher response: “what would you want to see?”

While the overall retail experience prototype had enough fidelity to answer nuanced questions about the environmental and service design, they were able to answer their low fidelity question about screens with a box cutter.

Fundamentally difficult

I helped design a patient alert system for a hospital, and before long, we needed to know: what is the right medium for alerts? SMS/text? Email? A dedicated pager? It sounds like a basic question—we didn’t even know what form our design should take. But was it easy to answer?

We could have sent out surveys, asking people their preference. However, there’s often a difference between what people say in a survey and what they do in real life. A patient’s response in a survey or interview might not match the reality of a busy hospital with cell-service dead zones, rules about phone use, and charged emotions. To give us good feedback, they had to really experience the options. So we got to work prototyping an alert system that sent SMS and email, and we engineered little pager-like prototypes which were GSM and WiFi enabled. The question in this case was simple and fundamental, but extremely high fidelity.

Overkill urge

Later in development, we may have very specific questions about functionality or desired behavior. On a different project which featured a list of people in a web interface, we wanted to learn about the desirability of search, how our users might sort the list, and what they might enter in the search field. Being a diligent Software Designer, I spent a day or two making column sorting and search fully functional in our prototype web app.

But once participants saw the sorting arrows and search field, they gave us the feedback we needed. They didn’t need to interact with the software at all. The question was so low fidelity, our prototype could have been a Sharpie sketch.

In practice

There are a few prompts I like to keep in mind as we move from learning goals to finished prototypes.

- What’s in our way? Design teams are curious by nature, so you may have a laundry list of questions leading up to research. But there are some questions that absolutely must be resolved before you can make progress confidently, while others are merely “interesting” or can be answered later. Prioritize the questions that will unblock your path—those are worth prototyping.

- Can we answer more than one question with each prototype? A prototype should be focused enough to direct a participant’s attention to the central concept of a design. But it’s usually possible to embed several questions without making a prototype difficult to grasp. One simple example: on a banking project, we sketched a celebration screen that might pop up after reaching a financial goal, and added a “Share” button to help us understand whether our users would be comfortable sharing financial achievements. Our questions around Celebration and Sharing were distinct, but paired nicely as a single sketch.

- Are our prototypes open-ended? If prototypes are questions embodied, ideally they are open-ended questions. The foamcore iPad invites a conversation. The “Share” button lets us ask “Would you share?” as well as “Where? With whom? Why?” If we had built a separate detailed sharing screen, we might have heard irrelevant feedback about Twitter versus Facebook. Unnecessary detail or polish can also lead participants to think our designs are more resolved than they really are—making them hesitant to question the basic premise or underlying concept.

- Do our prototypes set the scene? Extraneous detail is distracting, but our prototypes need enough information and fidelity to set the scene and help participants project themselves into our imagined scenario. The foamcore iPad only worked because participants were standing in our full-scale store prototype. The Share button needs something else on the screen to share—and the celebration screen wouldn’t work with a lorem ipsum title.

It can be difficult to find the sweet spot between distractingly specific and confusingly vague—that’s part of the art of prototyping. But when you’re stuck, it usually helps to return to the learning goal and ask “what is the fidelity of this question?”